When norovirus hits, it doesn’t just make people sick-it shuts down nursing homes, cancels school lunches, and empties hospital beds in days. In Melbourne, we’ve seen it happen: one staff member vomiting on a Friday, and by Monday, half the ward is down with stomach cramps and diarrhea. It’s not a coincidence. Norovirus is the most common cause of acute gastroenteritis in the U.S., and it’s just as relentless here in Australia. The CDC estimates 19 to 21 million cases every year. And here’s the scary part: you only need 18 virus particles to get infected. That’s less than a grain of salt.

How Norovirus Spreads-And Why It’s So Hard to Stop

Norovirus doesn’t care if you’re young, old, healthy, or sick. It spreads fast because it’s built to survive. You can catch it from touching a doorknob someone vomited on 12 hours ago. Or from eating a salad someone prepared while they were still feeling queasy. Or even from breathing in tiny droplets when someone vomits nearby. The virus sticks to surfaces for up to 12 days. It laughs at freezing temperatures and survives up to 140°F. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers? Useless. That’s why outbreaks in hospitals and aged care homes explode so quickly.Transmission breaks down like this: 62% comes from person-to-person contact. Another 23% is from food-especially ready-to-eat items like lettuce, sandwiches, or sushi handled by an infected worker. Only 10% comes from contaminated surfaces, and 5% from water. But here’s the twist: you can spread the virus before you even feel sick. And you keep shedding it for at least 48 hours after your vomiting stops. For some people-especially those with weak immune systems-that can stretch for weeks.

Stopping the Outbreak: The 4 Pillars of Control

There’s no magic bullet. Controlling norovirus means hitting it from all sides. Four things work together: isolation, hand hygiene, cleaning, and food safety.1. Isolate early, isolate long. If someone starts vomiting or has diarrhea, they need to be separated immediately. In healthcare settings, CDC guidelines say to put them in a single room. If that’s not possible, group all sick people together and keep them away from healthy ones. Don’t move asymptomatic residents-even if they seem fine, they could already be infected. Stay isolated for at least 48 hours after symptoms stop. In aged care homes, cancel group meals, activities, and outings until then.

2. Wash hands like your life depends on it. Soap and water. Not sanitizer. Alcohol-based gels don’t kill norovirus. You need to scrub for at least 20 seconds-long enough to sing ‘Happy Birthday’ twice. Wash after using the toilet, changing diapers, before eating, and before touching food. Place handwashing stations right outside affected rooms. During outbreaks, staff compliance drops by 25-30% because they’re overwhelmed. That’s when you need reminders, posters, and supervisors checking in.

3. Clean with bleach, not just disinfectant. Regular cleaners won’t cut it. You need chlorine bleach at 1,000 to 5,000 ppm. That’s 5 to 25 tablespoons of household bleach per gallon of water. Use it on all high-touch surfaces: door handles, bed rails, toilet flushers, light switches, faucets. Clean twice a day during an outbreak. For terminal cleaning after an outbreak, some hospitals now use hydrogen peroxide vapor systems-these reduce contamination by 99.9%. Don’t skip floors. Don’t skip trash bins. Don’t assume it’s clean because it looks clean.

4. Keep food handlers out of the kitchen. If someone has had vomiting or diarrhea, they can’t return to handling food for at least 48 hours. In hospitals and aged care, it’s 72 hours. No exceptions. This isn’t just policy-it’s survival. CDC data shows that food handlers are behind nearly a quarter of all outbreaks. And leafy greens? They’re the #1 culprit. Wash them, sure-but if they were handled by someone who was sick, even washing won’t help. The virus doesn’t wash off.

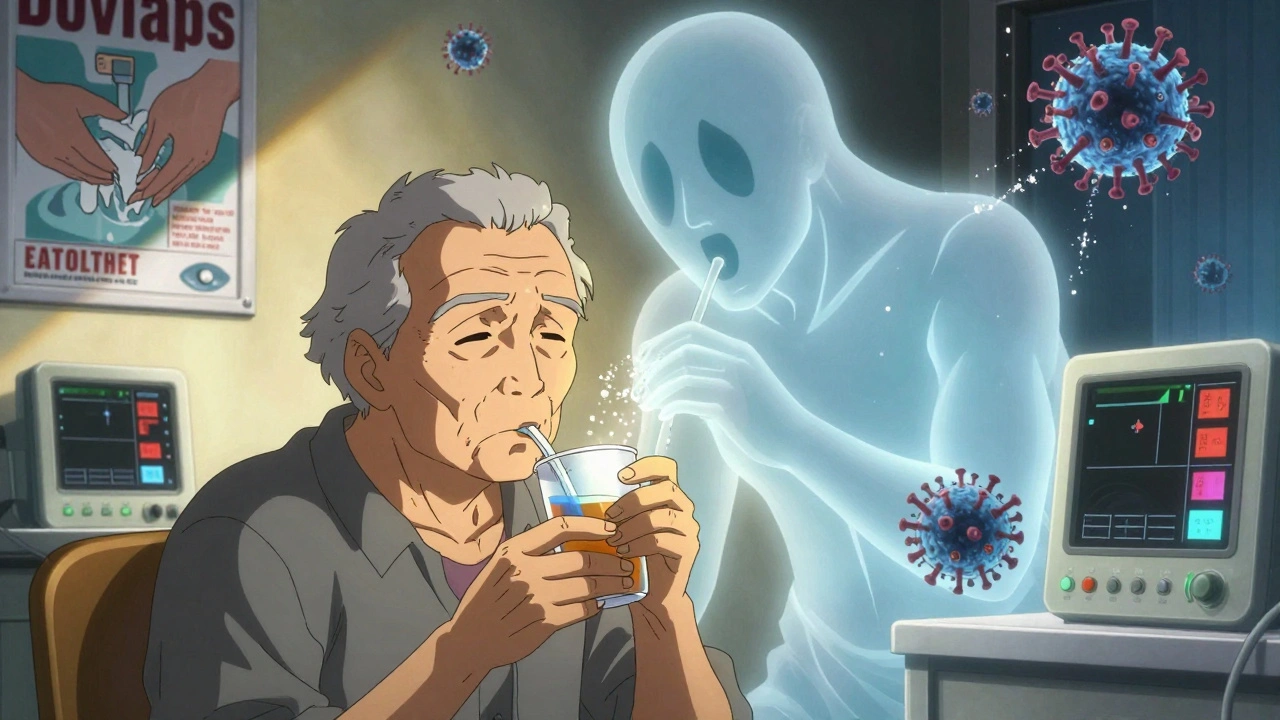

Hydration: The Lifesaver Nobody Talks About

People focus on stopping the virus. But the real killer isn’t the virus-it’s dehydration. Vomiting and diarrhea can drain fluids faster than you can drink them. Elderly patients, babies, and those with chronic illnesses can crash in hours.Oral rehydration solution (ORS) is the first line of defense. It’s not sports drinks. It’s not soda. It’s a precise mix of water, salt, sugar, and potassium. WHO standards say it should have 50-90 mmol/L sodium and 75-100 mmol/L glucose. You can buy it in packets at pharmacies, or make it at home: 1 liter of clean water, 6 teaspoons of sugar, half a teaspoon of salt. Stir well. Give small sips every 5-10 minutes. For children, give 50-100 mL after each episode of vomiting or diarrhea. For adults, aim for 200-400 mL after each loose stool.

If someone can’t keep fluids down, or they’re dizzy, have sunken eyes, or haven’t urinated in 8 hours-they need IV fluids. Hospitals use 0.9% saline or lactated Ringer’s. A 20 mL/kg bolus over 15-30 minutes can turn a collapsing patient around in minutes. Don’t wait. Don’t assume they’ll “get better on their own.”

Monitor elderly patients closely. Their thirst signal fades with age. They might not say they’re thirsty until they’re already dehydrated. Check urine output every 4-6 hours. Watch for confusion, dry mouth, low blood pressure. In long-term care, staff should be trained to spot these signs fast.

Who’s Most at Risk-and What to Do Differently

Not everyone reacts the same. Infants, older adults, and people with weakened immune systems are in danger zone.Infants and toddlers: Their tiny bodies lose fluid fast. Use ORS, not plain water. Watch for fewer wet diapers. If they’re listless or crying without tears, get help immediately.

Elderly in care homes: They’re the most likely to die from norovirus. Why? Dehydration, falls from dizziness, and existing heart or kidney problems. They need more frequent checks, not less. During winter outbreaks (November-March), staffing is low and risk is high. That’s when you need extra hands, even if it means pulling from other units.

Immunocompromised patients: Cancer patients, transplant recipients, those on chemotherapy-they can shed the virus for months. Isolation isn’t just for 48 hours. They need extended precautions. Staff need to know their status. And don’t assume they’re not contagious because they don’t look sick.

Visitors, Staff, and the Hidden Spreaders

Outbreaks don’t start with patients. They start with visitors. A grandparent visiting a loved one in hospital, not realizing they’re incubating the virus. Or a nurse who worked a double shift and didn’t wash hands properly.Restrict non-essential visitors during outbreaks. If someone must come in, make them wash hands before entering and after leaving. Give them a quick briefing: “If you’ve had diarrhea or vomiting in the last 48 hours, don’t come in.” Facilities that do this see 35% fewer secondary cases.

Staff training is non-negotiable. Within 24 hours of an outbreak, everyone-cleaners, cooks, aides, nurses-needs a 15-minute refresher on handwashing, PPE, and cleaning protocols. Document it. If you don’t, you’re not just risking lives-you’re risking your facility’s reputation.

What’s Next? Vaccines and Better Tools

There’s hope on the horizon. Takeda’s norovirus vaccine showed 46.7% effectiveness in phase 2 trials in 2022. If approved in 2025 as expected, it could be a game-changer-especially for nursing homes and hospitals. But until then, we’re stuck with the basics: soap, bleach, isolation, and hydration.The CDC’s 2023 update reminds us: no single measure works alone. You need all four pillars. And you need to do them right. One missed handwash. One diluted bleach solution. One staff member returning to work too soon. That’s all it takes.

It’s not glamorous. It’s not exciting. But if you do it right, you keep people alive.

Can alcohol hand sanitizer kill norovirus?

No. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers do not kill norovirus. The virus has a tough outer shell that alcohol can’t break down. The only effective method is washing hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds. This is especially critical after using the bathroom, before eating, and after caring for someone who’s sick.

How long should someone stay home after norovirus symptoms stop?

At least 48 hours after vomiting and diarrhea stop. For food handlers in healthcare or aged care settings, the rule is 72 hours. Even if you feel fine, you’re still shedding the virus. Returning too soon can start a new outbreak.

Can you get norovirus more than once?

Yes. There are many strains of norovirus, and immunity after infection is short-lived-usually only a few months. So even if you’ve had it before, you can catch it again. That’s why outbreaks keep happening in the same places.

What’s the best way to clean vomit or diarrhea?

Wear gloves and a mask. Remove solid waste with paper towels. Then clean the area with a bleach solution: 1,000-5,000 ppm chlorine (5-25 tablespoons of household bleach per gallon of water). Let it sit for 10 minutes before wiping. Wash linens and clothing in hot water and dry on high heat. Never use a vacuum or mop-these can spread particles into the air.

Is norovirus only a winter problem?

It’s most common in winter (November-March), especially in northern climates. But outbreaks can happen any time of year. In Australia, we see spikes in colder months, but outbreaks in aged care homes and childcare centers occur year-round. Don’t let your guard down in summer.

Can you catch norovirus from someone who doesn’t have symptoms?

Yes. About 30% of infected people never show symptoms but still shed the virus in their stool. That’s why asymptomatic people shouldn’t be moved between units during an outbreak-they might already be infected. Screening based on symptoms alone isn’t enough.

What to Do Right Now

If you’re in a home, school, or care facility:- Check handwashing stations-are they stocked with soap and paper towels?

- Review your cleaning log-when was the last time bleach was used on high-touch surfaces?

- Ask staff: do they know the 48-hour return-to-work rule?

- Keep ORS packets on hand in medical areas.

- Post simple signs: “Wash hands before eating. Wash hands after using the toilet.”

Norovirus doesn’t care about your budget, your staffing levels, or how busy you are. It only cares if you skip a step. One missed wash. One diluted bleach mix. One person back at work too soon. That’s all it takes.

Do it right. Every time.

Chad Kennedy

December 3, 2025 at 10:59Ugh, another one of these posts. I swear every time I see 'norovirus' I just want to throw my hands up. Why do people even bother? It's everywhere. You can't stop it. Just stay home and hope for the best.

Siddharth Notani

December 5, 2025 at 03:30Thank you for this comprehensive guide. In India, we often underestimate the role of hygiene in preventing outbreaks. Handwashing with soap remains the most effective, low-cost intervention. A simple 20-second scrub can save lives. 🙏

Cyndy Gregoria

December 6, 2025 at 03:57This is exactly what we need more of! 🙌 I work in a nursing home and we’ve been using bleach solutions daily since last winter. It’s not glamorous, but it works. Keep doing the boring stuff-it matters.

Mark Gallagher

December 6, 2025 at 23:51If you’re not using 5000 ppm bleach, you’re not serious about infection control. And if your staff are using hand sanitizer? That’s not just negligent-it’s criminal. America needs to stop pretending quick fixes exist.

Wendy Chiridza

December 7, 2025 at 00:09I’ve seen outbreaks in two different hospitals and the one thing that always breaks down is cleaning logs. People forget to write it down so nobody knows if it was done. Start tracking it. Simple. Essential.

Pamela Mae Ibabao

December 8, 2025 at 23:52Funny how everyone acts like norovirus is this mysterious monster. It’s just a virus. The real problem is lazy management and underpaid staff who can’t afford to stay home. Blame the system, not the pathogen.

Gerald Nauschnegg

December 9, 2025 at 09:48I had norovirus last year and I swear I got it from my neighbor’s kid. They didn’t even wash their hands after using the bathroom. I told the school. They didn’t care. You think they’re going to fix it? No. They’ll just blame the parents.

Erik van Hees

December 10, 2025 at 22:49Let me break this down for you. You need bleach. You need soap. You need isolation. You need hydration. You need to fire anyone who doesn’t follow protocol. And you need to stop letting people come back after 48 hours-72 is the bare minimum. I’ve read the CDC. I know what I’m talking about.

Casey Lyn Keller

December 11, 2025 at 21:38I don’t trust any of this. Bleach? They’re probably just trying to make us buy more chemicals. I’ve been drinking apple cider vinegar and it worked for me. And why is the CDC always pushing stuff? Maybe they’re in cahoots with the cleaning supply companies.

Jessica Ainscough

December 12, 2025 at 09:16I just wanted to say thank you for writing this. I’m a nurse and I’ve seen how fast this spreads. It’s scary. But when we do it right-soap, bleach, hydration-it actually works. We saved three elderly patients last month because we caught it early. It’s not perfect, but it’s enough.