When your kidneys start to fail, even small changes in your body’s sodium levels can become dangerous. Hyponatremia (low sodium) and hypernatremia (high sodium) aren’t just lab numbers-they’re real risks that can lead to falls, confusion, hospital stays, and even death in people with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Around 1 in 5 people with advanced CKD will develop one of these sodium disorders, and many don’t even know it until something serious happens.

Why Your Kidneys Control Your Sodium

Your kidneys don’t just filter waste-they’re your body’s main sodium and water regulators. Healthy kidneys adjust urine concentration based on how much salt and water you take in. If you drink too much water, they make dilute urine to get rid of the excess. If you’re low on water, they save it by making concentrated urine. This balance keeps your blood sodium between 135 and 145 mmol/L.But when CKD progresses, this system breaks down. By stage 4 or 5 (GFR under 30 mL/min), your kidneys can’t make concentrated urine anymore. They also struggle to flush out extra water. That means even a small increase in fluid intake can flood your system with water, diluting your sodium and causing hyponatremia. On the flip side, if you’re not drinking enough-or you’re losing water through fever, sweating, or medications-your body can’t replace it properly, and sodium climbs too high, leading to hypernatremia.

Hyponatremia: The Silent Threat in CKD

Hyponatremia-serum sodium below 135 mmol/L-is the most common sodium disorder in CKD, affecting 60-65% of cases. The biggest culprit? Your kidneys can’t excrete water fast enough. This gets worse if you’re on thiazide diuretics (like hydrochlorothiazide), which are often prescribed for high blood pressure but become ineffective and risky once GFR drops below 30.Many patients with CKD are told to cut back on salt, protein, and potassium to protect their kidneys. But cutting back too much can backfire. A 2023 Japanese study found that strict solute restriction lowers urine output, making it even harder for kidneys to get rid of excess water. This pushes sodium levels down further. In fact, 22% of hyponatremia cases in late-stage CKD patients are linked to overly aggressive dietary restrictions.

The symptoms are subtle at first: fatigue, nausea, headaches. But over time, low sodium causes brain swelling. Studies show hyponatremic CKD patients have a 35% higher risk of falls, a 67% higher risk of fractures, and nearly double the risk of death compared to those with normal sodium levels. Hospitalized patients with hyponatremia have a 28% higher mortality rate than those without it.

Hypernatremia: When You’re Too Dry

Hypernatremia-sodium above 145 mmol/L-is less common but just as dangerous. It usually happens when you’re not drinking enough water, or when you’re losing too much fluid through vomiting, diarrhea, or fever. In CKD, your kidneys can’t concentrate urine to save water, so you lose more than you should. Elderly patients with dementia or mobility issues are especially at risk because they may not feel thirsty or can’t reach water on their own.High sodium pulls water out of your brain cells, causing them to shrink. This can lead to confusion, seizures, coma, and even permanent brain damage. The key is to correct it slowly-no faster than 10 mmol/L per day. Rushing correction can cause cerebral edema, which is just as deadly as the original high sodium.

Three Types of Hyponatremia in CKD

Not all hyponatremia is the same. In CKD, it breaks down into three types:- Hypovolemic (15-20%): You’ve lost both sodium and water, but more sodium. This can happen with overuse of diuretics, vomiting, or rare salt-wasting conditions like milk-alkali syndrome.

- Euvolemic (60-65%): Your total body water is high, but your sodium level is low. This is the most common type in CKD. Your kidneys can’t excrete water, so fluid builds up. Thiazide diuretics are a major cause here.

- Hypervolemic (15-20%): You have too much total fluid and too much sodium, but the water is overwhelming the sodium. This happens in advanced CKD with severe swelling (edema) or when heart failure is also present.

Knowing which type you have changes how you treat it. Giving fluids to someone with hypervolemic hyponatremia makes it worse. Restricting fluids in someone with hypovolemic hyponatremia can be deadly.

Treatment: Less Is Often More

There’s no one-size-fits-all fix. Treatment has to match your kidney function, your symptoms, and your volume status.For hyponatremia: Fluid restriction is the first step. If you’re in stage 4 or 5 CKD, limit fluids to 800-1,000 mL per day. In earlier stages, you might be allowed up to 1,500 mL. Never drink more than your kidneys can handle. Sodium supplements are rarely needed-unless you have a salt-wasting condition, in which case 4-8 grams of sodium chloride per day may be prescribed. Correction speed is critical: raise sodium no more than 4-6 mmol/L in 24 hours. Faster than that, and you risk osmotic demyelination syndrome-a rare but devastating brain injury.

For hypernatremia: Rehydrate slowly with water or IV fluids. The goal is to bring sodium down by no more than 10 mmol/L in 24 hours. Use plain water or half-normal saline. Avoid sugary drinks or salty broths.

Diuretics need careful review. Loop diuretics (like furosemide) are safer than thiazides in advanced CKD because thiazides don’t work well when GFR is low-and they increase hyponatremia risk. The FDA warns against using thiazides in patients with eGFR under 30. Vasopressin blockers (vaptans) are off-limits in advanced CKD because your kidneys can’t respond to them.

Why Diet Alone Isn’t Enough

Patients are often told to follow a “low-sodium, low-potassium, low-protein” diet. But these goals conflict. Cutting protein reduces urea, which your kidneys use to draw water out. Less urea means less water excretion-worsening hyponatremia. Cutting sodium too hard can trigger salt-wasting, especially in older adults.A 2020 study found patients need 3-6 sessions with a renal dietitian just to understand what to eat. Many think “no salt” means no flavor, so they avoid all processed foods and even table salt-but end up drinking too much water, thinking it’s healthy. That’s a recipe for hyponatremia.

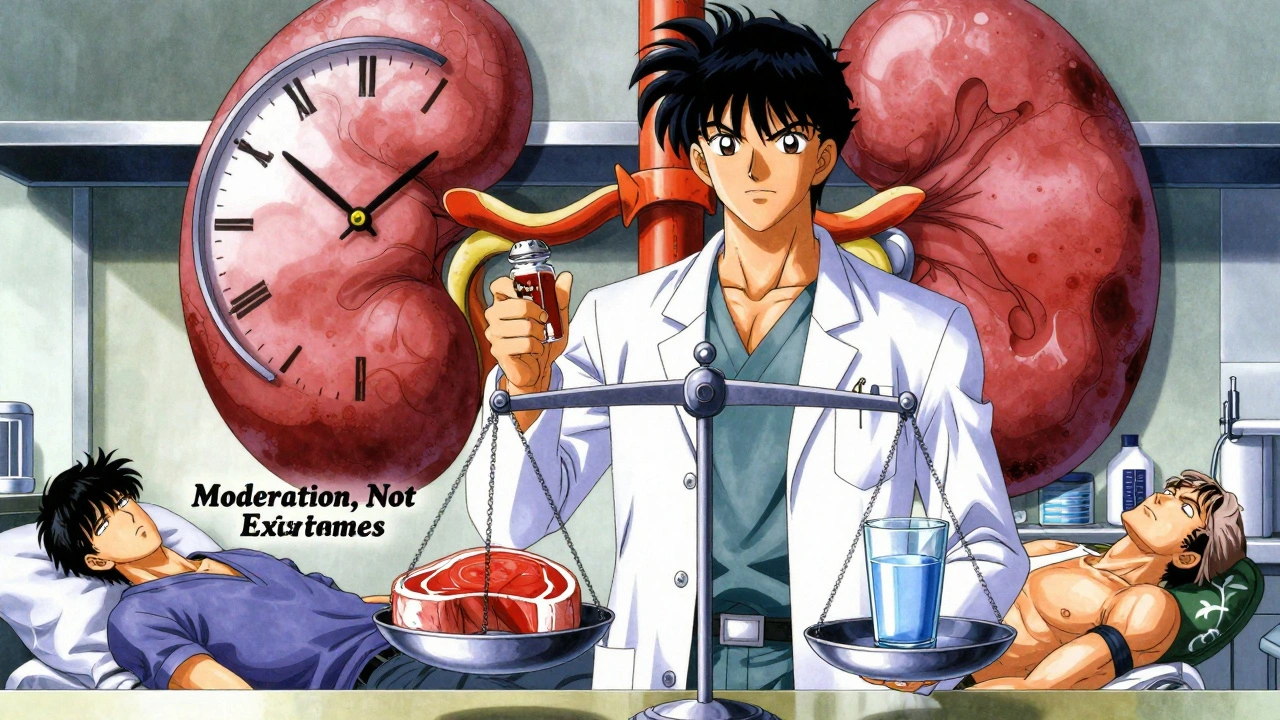

Instead of blanket restrictions, focus on balance. Eat enough protein to maintain muscle, keep sodium at moderate levels (2-3 grams/day), and drink only when thirsty-not because you’re told to “drink 8 glasses.”

The New Tools Changing the Game

In 2023, the FDA approved a wearable sodium monitoring patch for CKD patients. It measures interstitial sodium continuously and correlates with blood levels at 85% accuracy. This means doctors can see sodium trends over days, not just one lab test. It’s especially helpful for catching early drops before symptoms show.Guidelines are also changing. The 2024 KDIGO conference is pushing for individualized fluid targets based on your remaining kidney function-not a fixed number for everyone. Research is also exploring the gut-kidney axis: early data suggests your intestines might help handle sodium when kidneys fail, opening doors for new therapies.

What You Can Do Today

If you have CKD:- Ask your nephrologist for a sodium blood test every 3-6 months-even if you feel fine.

- Keep a daily fluid log. Note how much you drink and any swelling or weight gain.

- Don’t restrict sodium unless your doctor says so. Avoid extreme low-sodium diets.

- Review all your medications. Thiazide diuretics are risky in advanced CKD.

- Work with a renal dietitian. They can help you balance sodium, protein, and fluid without harming you.

- Watch for symptoms: confusion, nausea, muscle cramps, dizziness, or sudden weight gain.

Hyponatremia and hypernatremia aren’t inevitable in CKD. But they’re easy to miss-and deadly if ignored. The key isn’t just treating the number-it’s understanding how your kidneys, your diet, and your body’s water balance all fit together.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can drinking too much water cause hyponatremia in kidney disease?

Yes. In advanced kidney disease, your kidneys can’t flush out excess water efficiently. Drinking more than 1,000 mL per day can dilute your sodium levels, especially if you’re on certain diuretics or following overly strict low-solute diets. Even 2 liters a day can be dangerous if your GFR is below 30.

Is low sodium always bad for people with kidney disease?

Not always-but it’s always a warning sign. Mild hyponatremia (130-134 mmol/L) may not cause symptoms but still increases your risk of falls, fractures, and death. In CKD, even small drops in sodium are linked to worse outcomes. It’s not the low number itself that’s dangerous-it’s what it says about your body’s ability to handle water and salt.

Why are thiazide diuretics risky in CKD?

Thiazides work best when kidney function is normal. Once GFR drops below 30 mL/min, they become ineffective and can cause dangerous drops in sodium. The FDA warns against their use in advanced CKD because they’re linked to 25-30% of euvolemic hyponatremia cases. Loop diuretics like furosemide are safer and more effective at this stage.

Can I use salt substitutes if I have kidney disease?

Be very careful. Most salt substitutes replace sodium chloride with potassium chloride. In CKD, your kidneys can’t clear potassium well, which can lead to life-threatening hyperkalemia. Always check with your doctor before using any salt substitute.

How fast should sodium be corrected in kidney disease?

For hyponatremia, correct no faster than 4-6 mmol/L in 24 hours. For hypernatremia, no faster than 10 mmol/L in 24 hours. Too fast can cause brain damage-either swelling from rapid correction of high sodium, or osmotic demyelination from too-rapid correction of low sodium. This is why treatment must be guided by a nephrologist.

Do I need to avoid all salt if I have kidney disease?

No. Most people with CKD should aim for 2-3 grams of sodium per day-not zero. Extremely low sodium diets (under 1.5 grams) can worsen hyponatremia by reducing urine output and impairing free water excretion. The goal is moderation, not elimination.

What’s the biggest mistake doctors make with sodium in CKD?

Applying standard hyponatremia protocols to CKD patients without adjusting for reduced kidney function. Many doctors treat hyponatremia the same way they would in a healthy person-by giving fluids or salt. But in CKD, the kidneys can’t handle it. This leads to 12-15% of osmotic demyelination cases in CKD patients, which are often preventable with smarter, individualized care.

val kendra

December 4, 2025 at 20:19I had no idea hyponatremia was so common in CKD. My mom’s nephrologist never mentioned it until she fell and broke her hip. Turns out her sodium was 129. Scary how silent it is.

Now we track fluids like it’s a science project. 800ml max. No more "just drink water" advice.

Also ditched the thiazide. Switched to furosemide and life’s better.

George Graham

December 6, 2025 at 17:22Thanks for writing this. My dad’s in stage 4 and we’ve been terrified of messing up his diet. We thought low sodium = good. Turns out we were making it worse.

Just booked him a session with a renal dietitian. Feels like we finally have a map instead of guessing in the dark.

John Filby

December 7, 2025 at 00:53Wait so salt substitutes are dangerous?? 😱 I’ve been using those potassium ones for years thinking I was being healthy. My nephrologist is gonna kill me.

Also why is no one talking about this wearable patch?? That sounds like magic. I want one.

Jenny Rogers

December 7, 2025 at 13:15It is profoundly concerning that the medical establishment continues to promote one-size-fits-all dietary dogma in the face of overwhelming physiological evidence to the contrary. The very notion that patients should restrict sodium without individualized assessment reflects a systemic failure in nephrological education.

Furthermore, the normalization of thiazide use in advanced CKD-despite FDA warnings-is not merely negligent, it is ethically indefensible. One cannot treat a failing organ system with protocols designed for a healthy one.

Until clinicians recognize that renal physiology is not a static algorithm but a dynamic, context-dependent equilibrium, we will continue to see preventable iatrogenic harm.

Rachel Bonaparte

December 8, 2025 at 01:31Okay but have you heard about the pharmaceutical companies pushing this "fluid restriction" nonsense? 🤔 I read a whistleblower report that said Big Pharma loves hyponatremia because it creates endless cycles of hospital visits and expensive IV drips.

And that "wearable patch"? Totally a surveillance tool disguised as medicine. They’re tracking your sodium to sell you more meds.

Also, why are we letting doctors control our water intake? Water is freedom. You don’t need a nephrologist to tell you when you’re thirsty. 🌊🚫

My cousin’s grandma drank 3 liters a day and lived to 92. Coincidence? I think not.

Chase Brittingham

December 8, 2025 at 09:04This is exactly the kind of info I wish I’d had 2 years ago. My brother’s on dialysis and we were stressing over every gram of salt. Turns out he just needed to stop drinking Gatorade at 2am.

Also-thank you for mentioning the gut-kidney axis. That’s the future. I’ve been reading up on microbiome stuff and it’s wild how connected everything is.

Keep sharing this stuff. Real talk saves lives.

Bill Wolfe

December 9, 2025 at 18:49Let me just say-most people don’t understand that sodium isn’t the enemy, it’s the *balance*. And if you’re not reading KDIGO guidelines like gospel, you’re just winging it with your life.

Also, the fact that thiazides are still being prescribed to eGFR <30 patients? That’s not ignorance, that’s malpractice. I’ve seen 3 patients with osmotic demyelination because their docs thought "low sodium = fix with salt".

And don’t get me started on the dietitians who still tell patients to eat "low-sodium" processed food. Those things are full of hidden phosphorus and potassium. You’re trading one poison for another.

Knowledge is power. Read the papers. Stop trusting your GP.

Benjamin Sedler

December 11, 2025 at 04:02So let me get this straight-you’re telling me drinking less water might save my life… but only if I’m not already dehydrated from my meds… and only if my kidneys are still kinda working… and only if I don’t have heart failure… and only if I’m not elderly and forgetful…

So basically, if you’re CKD, your body is a Russian roulette chamber and the doctor just handed you a loaded gun labeled "fluid restriction"?

Also, who the hell decided 800ml is the magic number? Why not 798? Or 802? Is this science or astrology?

Also, I’m pretty sure my cat drinks more than that. She’s fine.

zac grant

December 11, 2025 at 16:11Big picture: CKD isn’t just about GFR numbers. It’s about volume status, solute load, and renal reserve. Hyponatremia in stage 4/5 is usually euvolemic-fluid overload without edema. That’s why fluid restriction > sodium restriction.

Thiazides = useless past GFR 30. Loop diuretics = better, but still don’t fix the root. Vaptans = contraindicated. Period.

The wearable patch? Game-changer. Real-time sodium trends > single lab draw. We’re moving from reactive to proactive management.

And yeah-protein restriction can worsen hyponatremia by lowering urea-driven osmotic gradient. That’s nephro 101. Still overlooked by 80% of PCPs.

TL;DR: Balance > restriction. Individualize > generalize.