QT Prolongation Risk Calculator

Patient Risk Assessment

Risk Assessment Results

Important: This tool provides general guidance only. Always consult clinical guidelines and monitor patients appropriately.

When you’re dealing with severe nausea from chemotherapy, surgery, or a bad stomach bug, ondansetron works fast. It’s the go-to drug for many doctors because it stops vomiting better than most alternatives. But behind that quick relief is a hidden danger: ondansetron can stretch out your heart’s electrical cycle - a change called QT prolongation - and in rare cases, trigger a deadly heart rhythm called torsades de pointes. This isn’t theoretical. It’s happened. And it’s preventable.

What QT Prolongation Actually Means

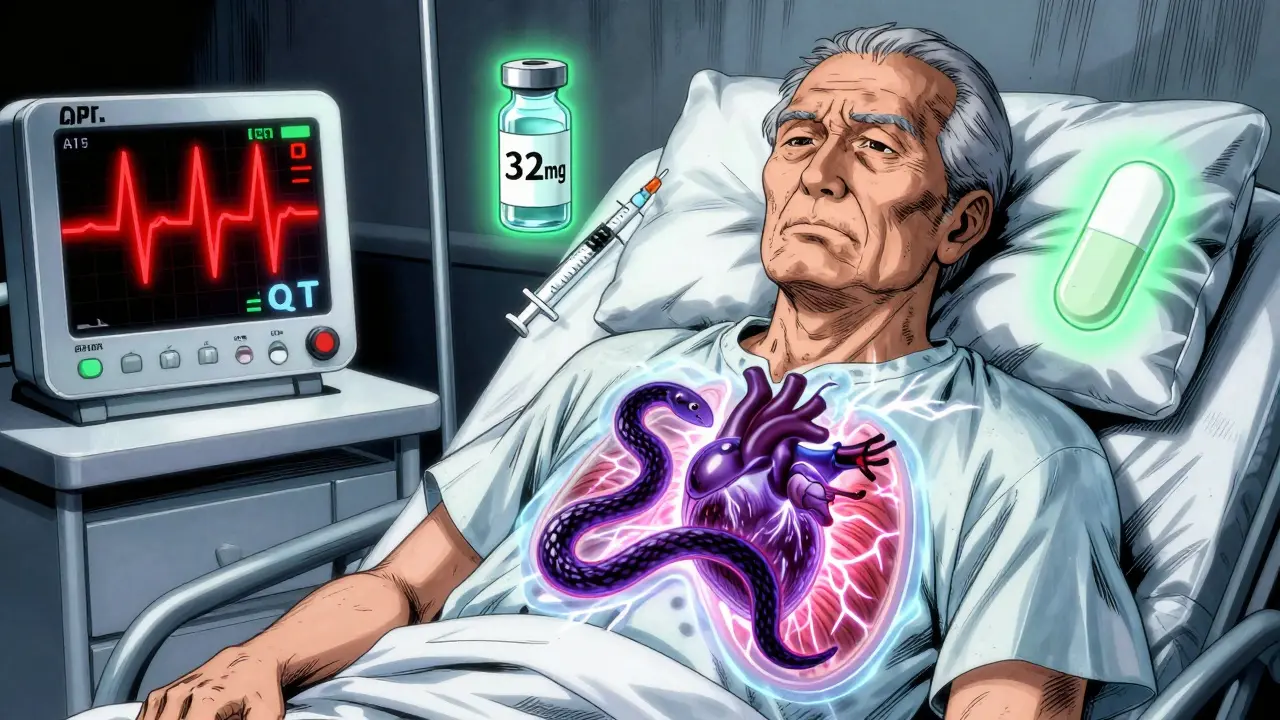

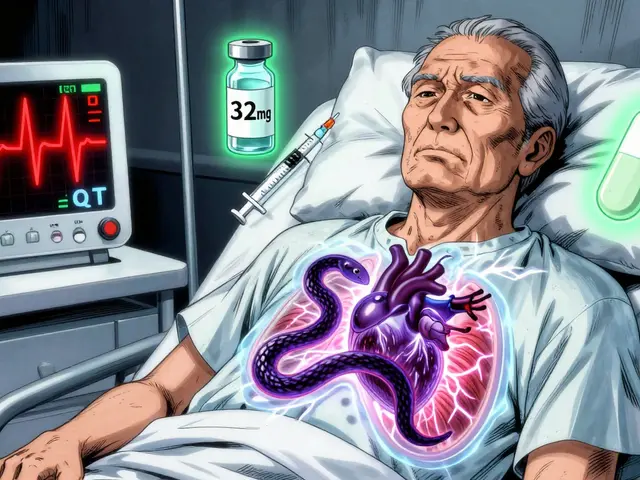

Your heart doesn’t just beat - it recharges. After each contraction, it needs time to reset before the next beat. That reset is measured as the QT interval on an ECG. When that interval gets too long, the heart’s electrical system becomes unstable. It can skip a beat, flip into a wild, uncoordinated rhythm, or even stop. That’s torsades de pointes. It’s rare, but when it happens, it kills quickly. About 1 in 500 people who get a big IV dose of ondansetron will show a dangerous QT lengthening. For someone already at risk, that number jumps.Why Ondansetron Does This

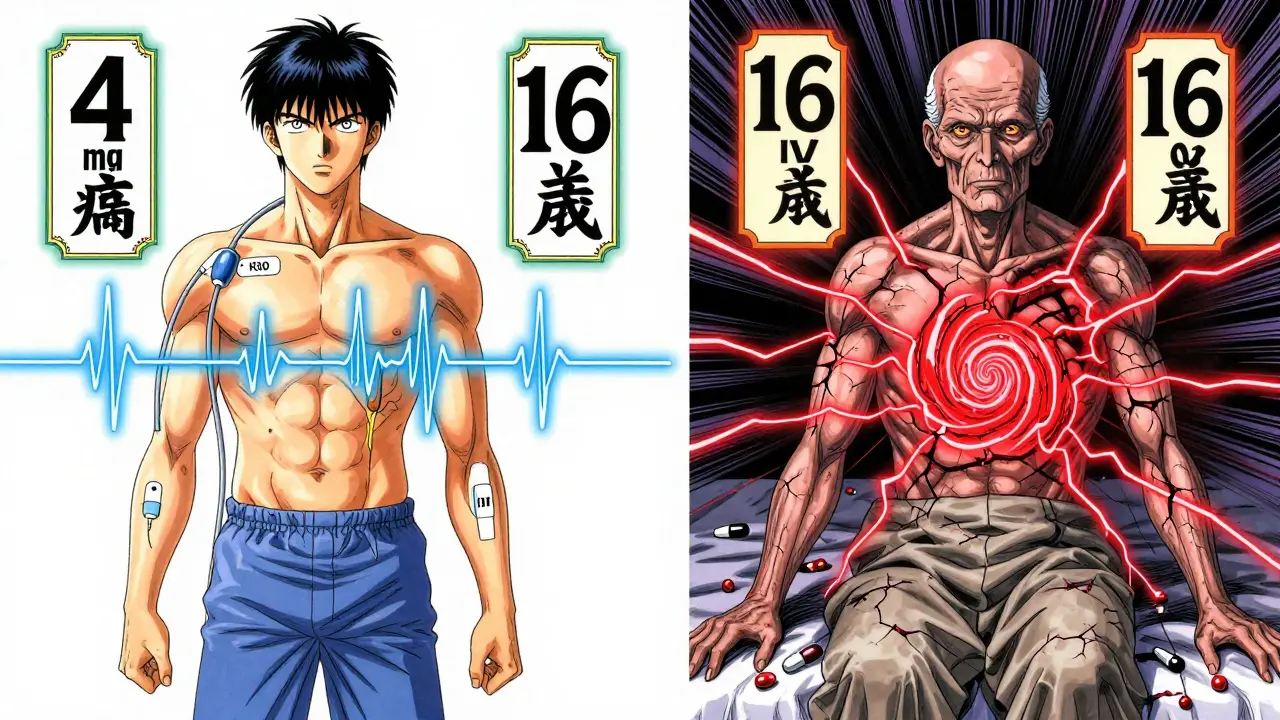

Ondansetron blocks serotonin receptors to calm nausea. But it also blocks a specific potassium channel in heart cells - the hERG channel. That’s the same channel that controls how fast the heart recharges. When it’s blocked, potassium can’t leave the cell quickly enough. The result? The heart takes longer to reset. The longer the reset, the higher the chance of a dangerous rhythm. Studies show that a single 32 mg IV dose of ondansetron can push the QTc interval up by 20 milliseconds. That’s not small. For context, a 10 ms increase is linked to a 5-7% higher risk of sudden cardiac events. The FDA banned the 32 mg IV dose in 2012 after clear evidence showed it caused dangerous spikes. Even 16 mg can be risky. The safe dose? For most people, 4 to 8 mg IV. Oral doses are safer - up to 24 mg is considered low risk because absorption is slower.Who’s Most at Risk

Not everyone who gets ondansetron is in danger. But some groups are walking a tightrope:- People with congenital long QT syndrome

- Those with heart failure or slow heart rates (bradycardia)

- Patients with low potassium or magnesium - even mild drops matter

- Older adults, especially over 75

- Anyone already on other QT-prolonging drugs: antibiotics like azithromycin, antidepressants like citalopram, or even some antifungals

How Other Antiemetics Compare

Ondansetron isn’t the only antiemetic that can mess with your heart - but it’s one of the most commonly used. Here’s how others stack up:| Drug | Class | Max QTc Increase (ms) | IV Dose Risk | Preferred in Cardiac Risk? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ondansetron | 5-HT3 antagonist | 20 | High (≥16 mg) | No |

| Granisetron | 5-HT3 antagonist | 8-10 | Moderate | Yes |

| Dolasetron | 5-HT3 antagonist | 25-30 | Very High | No |

| Palonosetron | 5-HT3 antagonist | 9.2 | Low | Yes |

| Droperidol | Butyrophenone | 15-20 | High | Caution |

| Prochlorperazine | Phenothiazine | 10-15 | Moderate | Yes (with monitoring) |

| Dexamethasone | Corticosteroid | 0-2 | Very Low | Yes |

What Hospitals Are Doing Now

Since the FDA warning in 2012, hospitals have changed how they use ondansetron. A 2022 survey found that 92% of U.S. hospitals now have formal protocols. Here’s what they look like in practice:- Check baseline ECG before giving IV ondansetron if the patient is over 65, has heart disease, or takes other QT-prolonging drugs.

- Don’t give more than 8 mg IV to anyone with risk factors - even if they’re otherwise healthy.

- Correct low potassium (<3.5 mEq/L) or magnesium (<1.8 mg/dL) before dosing. These aren’t just numbers - they’re triggers.

- Monitor ECG for 4 hours after IV administration in high-risk patients. Some hospitals use automated alerts if QTc rises more than 15 ms from baseline.

- Pharmacists now verify all high-dose orders. In 87% of academic centers, a pharmacist must sign off before a 16 mg IV dose is given.

What You Should Ask Your Doctor

If you’re about to get ondansetron - whether in the hospital, ER, or clinic - here’s what to ask:- “Is this dose necessary? Can we use a lower one?”

- “Have my electrolytes been checked?”

- “Do I have any heart conditions or take other meds that affect my heart rhythm?”

- “Will I need an ECG before or after?”

- “Are there safer alternatives for my situation?”

The Bigger Picture

Ondansetron is still the most prescribed antiemetic in the U.S. - 18.7 million prescriptions in 2022. But IV use has dropped 22% since 2012. Why? Because people started paying attention. The market for safer alternatives like palonosetron and aprepitant has grown by over 15% annually. Oncology guidelines now list palonosetron as the top choice for patients with cardiac risk. Research is moving even further. The NIH is running a trial called QT-EMETIC, testing whether genetic testing (specifically for CYP2D6 poor metabolizers) can predict who’s most likely to have dangerous QT prolongation. Early results suggest some people are genetically wired to process ondansetron slower - meaning even normal doses can pile up in their system and push their QT interval into danger.Bottom Line

Ondansetron saves lives by stopping vomiting. But it can also end them - if used carelessly. The risk isn’t in the drug itself. It’s in the dose, the patient, and the context. A single 8 mg IV dose in a healthy young person? Low risk. A 16 mg IV dose in a 78-year-old with heart failure and low potassium? That’s a recipe for disaster. The fix isn’t to stop using ondansetron. It’s to use it wisely. Check the ECG. Check the electrolytes. Use the lowest effective dose. Consider alternatives. And never, ever give 32 mg IV. That dose should be banned from every hospital formulary - and it mostly is. Now, make sure your doctor knows why.Can I take ondansetron orally if I’m worried about my heart?

Yes, oral ondansetron is much safer than IV. The FDA says single oral doses up to 24 mg don’t significantly prolong the QT interval in most people. That’s because the drug enters your bloodstream slowly, avoiding the sharp spike that IV delivery causes. Still, if you have severe heart disease or are taking other QT-prolonging drugs, talk to your doctor before taking high oral doses.

What if I already got a high dose of ondansetron? Should I panic?

Not necessarily. Most people who get a 16 mg IV dose won’t have problems. But if you have risk factors - heart disease, low potassium, or are on other heart-affecting meds - you should get an ECG within 2-4 hours. Watch for symptoms like dizziness, palpitations, fainting, or sudden shortness of breath. If you feel any of those, go to the ER immediately. Torsades can come on fast.

Is ondansetron safe during pregnancy?

Ondansetron is commonly used for morning sickness, and studies haven’t shown a clear link to birth defects. But its effect on the fetal heart isn’t well studied. The FDA hasn’t changed its stance, but some OB-GYNs now prefer doxylamine-pyridoxine (Diclegis) as first-line because it has no known cardiac risks. If you’re pregnant and need something stronger, ask your doctor about alternatives and whether an ECG is needed.

Why do some doctors still use 16 mg IV?

Because they haven’t updated their training. Many learned to use 16 mg as standard before the 2012 FDA warning. Others believe it’s more effective for severe nausea. But evidence shows 8 mg works just as well in most cases, and 16 mg doesn’t improve outcomes - it just raises risk. Hospitals with pharmacist-led protocols have cut high-dose use by over 70%. It’s not about tradition - it’s about safety.

Are there any natural alternatives to ondansetron?

There’s no natural substitute that works as reliably as ondansetron for chemotherapy or post-op nausea. Ginger can help mild nausea, and acupressure wristbands may offer some relief, but they won’t stop severe vomiting. For high-risk patients, dexamethasone is the safest medical alternative. Don’t skip prescribed treatment for unproven remedies if you’re facing serious nausea.

Candice Hartley

January 27, 2026 at 07:10This is terrifying. I had ondansetron after chemo and never knew my heart was on a tightrope. 😳

suhail ahmed

January 28, 2026 at 18:08Man, this is the kind of post that makes you pause. Ondansetron’s like that flashy friend who gets you through the night but leaves chaos in their wake. 🌪️ We need better awareness - especially in ERs where they just reach for it like it’s aspirin.

Conor Flannelly

January 29, 2026 at 18:14It’s fascinating how a drug designed to calm the gut can destabilize the heart. The hERG channel isn’t just a biological detail - it’s a silent gatekeeper. Block it, and you’re gambling with the rhythm of life. We treat nausea like a minor nuisance, but the body doesn’t compartmentalize that way. It all connects.

Anjula Jyala

January 31, 2026 at 10:21If you're giving >8mg IV without checking QTc you're not a clinician you're a liability. Baseline ECG is non negotiable period

Kegan Powell

February 1, 2026 at 23:13I’ve seen this play out in the ICU - a patient gets 16mg because they’re throwing up everywhere and boom 520ms QTc. No one meant to hurt anyone but the system’s set up for speed not safety. We gotta fix the culture not just the dosing

Murphy Game

February 3, 2026 at 10:08They knew. They always knew. The FDA ban was just damage control. Big Pharma doesn’t care about torsades as long as the script keeps printing. Watch how they push oral forms now - same molecule different delivery same risk different PR spin. 🕵️♂️

Kirstin Santiago

February 4, 2026 at 02:11I’m so glad this is getting attention. I work in oncology and we switched to palonosetron for anyone over 65 or with cardiac history. It’s not perfect but the QT risk is so much lower. Small changes save lives.

Patrick Merrell

February 4, 2026 at 08:02You people act like this is news. I’ve been screaming about this since 2013. Nurses get trained on this in 20 minutes and then they give 16mg like it’s water. Someone’s gonna die on your watch and you’ll say 'I didn’t know'. You knew.

Paul Taylor

February 5, 2026 at 06:14I work in a hospital that still uses ondansetron like it’s candy and I’m tired of it. We’ve got patients on azithromycin and citalopram getting 8mg IV and no ECG. The protocol says check QTc but no one checks it because it takes 10 minutes and the family is mad the patient is still puking. We need better systems not better reminders. We need to stop treating medicine like a race and start treating it like a responsibility

Conor Murphy

February 5, 2026 at 11:53Paul you’re so right. It’s not about the drug. It’s about the rhythm of care. We rush through checks because we’re overworked and under-supported. But when a heart flips - it’s not a mistake. It’s a failure of the whole system. We need to stop blaming individuals and start redesigning workflows. And maybe… just maybe… give nurses the power to say no when the dose is wrong.