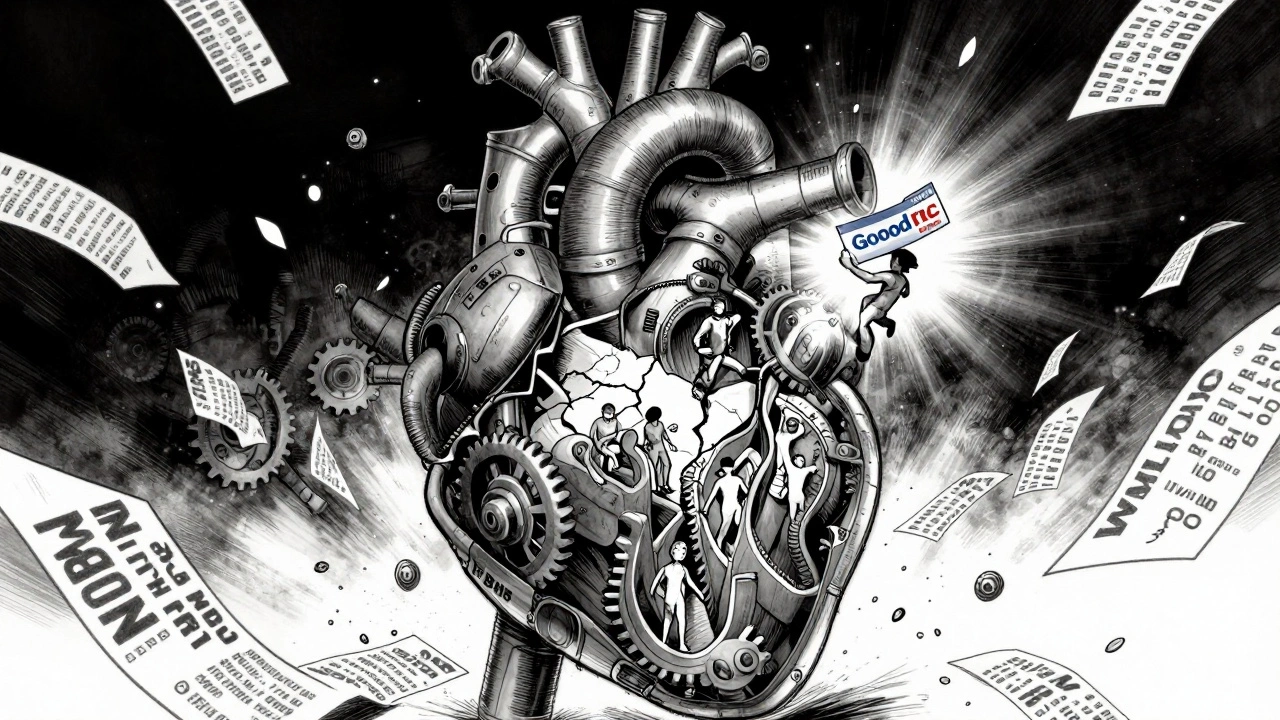

Ever wonder why your generic blood pressure pill costs $12 in Texas but $45 in California-even though it’s the exact same medicine? It’s not a mistake. It’s not a glitch. It’s the system. Across the U.S., the price of the same generic drug can swing by more than 300% depending on which state you live in. And it’s not just about where you buy it. It’s about who’s controlling the pipeline between the manufacturer and your pharmacy counter.

How the Same Drug Costs So Much More in Some States

Generic drugs are supposed to be cheap. They’re copies of brand-name pills that have lost patent protection. The science is identical. The ingredients are identical. But the price? Not even close. In 2020, generics made up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. But they accounted for just 18% of total drug spending. That sounds good-until you realize that millions of people are still paying way more than they should. A 2021 study found that the wholesale price of a generic drug, one year after it hits the market, averages about 45% of the brand-name version. But what you pay at the pharmacy? Around 66%. That gap? That’s where the middlemen take their cut. States don’t control drug manufacturing. But they do control how Medicaid pays for drugs, how pharmacies are licensed, and whether they force companies to reveal pricing data. That’s where the differences start.Pharmacy Benefit Managers Are the Hidden Drivers

You’ve probably never heard of Pharmacy Benefit Managers, or PBMs. But they’re the ones pulling the strings. PBMs are middlemen between drug makers, insurers, and pharmacies. They negotiate prices, manage formularies, and collect rebates. And they’re not required to tell anyone how those deals work. In states with weak transparency laws, PBMs can set up secret contracts that inflate prices. A 2022 study from the USC Schaeffer Center found that U.S. consumers overpay for generics by 13% to 20% because of these opaque practices. And those overcharges aren’t spread evenly. In states like California and Vermont, which passed laws requiring PBMs to disclose pricing terms, patients pay 8% to 12% less on average than those in states like Florida or Ohio, where no such rules exist. Even worse, some PBMs own pharmacies. They’ll push you to fill prescriptions at their own stores-where they get to keep the full markup. Meanwhile, independent pharmacies get squeezed out. That reduces competition. And less competition means higher prices.Medicaid Reimbursement Rules Vary Wildly

Medicaid pays for most generic drugs for low-income patients. But each state sets its own reimbursement rate. Some use the National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (a federal benchmark that tracks what pharmacies actually pay for drugs, updated monthly). Others use older, outdated benchmarks. Some even tie payments to the Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC)-a price list drugmakers publish that often has nothing to do with real market prices. In states using NADAC, pharmacies get paid closer to what they actually pay for the drug. In states using WAC, they get paid way more-and that extra money often ends up in the PBM’s pocket, not yours. That’s why a 30-day supply of generic lisinopril might cost $4 at a pharmacy in Minnesota but $18 in Alabama. It’s not the pharmacy charging more. It’s the state’s reimbursement system letting the middleman keep the difference.

State Laws Tried to Fix This-Then Got Blocked

In 2017, Maryland passed a law making it illegal for drug companies to charge “unconscionable” prices for generic drugs. It was a direct attempt to stop price gouging. Within a year, a federal appeals court struck it down. Why? Because the court said states can’t interfere with interstate commerce. That ruling sent shockwaves through state legislatures. Nevada tried something similar for diabetes drugs. The lawsuit was dropped. Experts believe the drugmakers and PBMs threatened to sue under the Defend Trade Secrets Act-forcing the state to back down before any data could be made public. Now, 18 states have created “drug affordability boards.” These boards can review drug prices and recommend actions. But they can’t set prices. They can’t force companies to lower costs. They can only study them. That’s not enough to stop the bleeding.Why Paying Cash Can Save You Hundreds

Here’s the most surprising part: if you’re paying for a generic drug out of pocket, you often pay less than if you use your insurance. In 2020, 4% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. were paid in cash. Ninety-seven percent of those were for generic drugs. Why? Because insurance copays are often set higher than the actual cash price. A 2022 GoodRx analysis showed that for common generics like atorvastatin, metformin, and levothyroxine, paying cash saved people 30% to 70% compared to using insurance. In states like Texas and Georgia, cash prices for generics are often under $10. In New York or Washington, the same pills might cost $30 or more through insurance. But if you use GoodRx or a discount pharmacy like Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company, you can bypass the PBM system entirely. You pay the real market price-no middleman, no hidden fees.What’s Changing in 2025?

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 brought some relief-but only for Medicare patients. Starting in 2025, seniors on Medicare will pay no more than $35 a month for insulin and cap their total out-of-pocket drug spending at $2,000 a year. That’s huge. But it only helps 32% of the population. For everyone else, the rules are still a mess. The FDA approved 843 generic drugs in 2017-the most ever. But those savings didn’t reach everyone equally. States with strong transparency laws captured more of the savings. Others didn’t. Experts now believe the real opportunity lies in regulating PBMs-not drugmakers. The USC Schaeffer Center says, “Savings from generic markets won’t hurt innovation. They’ll hurt the middlemen.” That’s why states like California and Maine are pushing for PBM licensing requirements, banning gag clauses that stop pharmacists from telling you about cheaper cash prices, and forcing PBMs to pass rebates to consumers.

What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t need to wait for a law to change. Here’s how to save money today:- Use GoodRx or SingleCare to compare cash prices in your area. Enter your drug, zip code, and see what pharmacies charge.

- Ask your pharmacist: “What’s the cash price?” Don’t assume your copay is the best deal.

- If you’re on Medicare, check if your drug is covered under the $35 insulin cap or the $2,000 out-of-pocket limit.

- Consider switching to a direct-purchase pharmacy like Cost Plus Drug Company if you take long-term generics.

- Advocate for state transparency laws. Contact your state representative. Ask them to support PBM reform.

Why This Isn’t Going Away Soon

Drug pricing isn’t broken because of greed. It’s broken because it’s designed this way. PBMs profit from complexity. States are limited by federal law. Drugmakers don’t control the final price. The system is a maze-and the people paying the most are the ones who don’t know how to navigate it. But knowledge is power. If you know that the same pill costs $12 in one state and $45 in another, you can choose differently. You can pay cash. You can shop around. You can demand transparency. And you’re not alone-millions are doing the same thing, one prescription at a time.Why do generic drug prices vary so much between states?

Generic drug prices vary by state because each state sets its own Medicaid reimbursement rates, enforces different transparency laws for Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs), and has varying levels of pharmacy competition. States like California and Vermont require PBMs to disclose pricing, leading to lower out-of-pocket costs. In contrast, states with weak regulations allow PBMs to set secret contracts that inflate prices. The federal NADAC benchmark is used in some states but not others, further widening the gap.

Is it cheaper to pay cash for generic drugs than to use insurance?

Yes, often. Many insurance plans set copays higher than the actual cash price of generics. A 2022 GoodRx analysis found that paying cash saved patients 30% to 70% on common generics like atorvastatin and metformin. This is especially true in states with high PBM markups. Cash prices through services like GoodRx or Cost Plus Drug Company bypass the insurance middleman entirely, giving you the real market price.

What role do Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) play in price differences?

PBMs negotiate drug prices between manufacturers and pharmacies, but they operate with little transparency. In states without disclosure laws, PBMs can keep rebates for themselves, set inflated reimbursement rates, and own pharmacies to steer patients toward higher-cost options. This creates price distortions that vary by state. USC Schaeffer Center research shows PBMs and their parent companies overcharge consumers by 13% to 20% on generics due to these opaque practices.

Why did Maryland’s generic drug pricing law get struck down?

In 2018, a federal appeals court ruled Maryland’s law banning “unconscionable” generic drug prices unconstitutional because it interfered with interstate commerce. The court said states can’t regulate prices of drugs that cross state lines. This decision discouraged other states from passing similar laws, shifting focus toward less direct approaches like transparency requirements and PBM licensing instead of direct price controls.

Does the Inflation Reduction Act help with generic drug prices?

Only for Medicare beneficiaries. Starting in 2025, seniors on Medicare will pay no more than $35 per month for insulin and cap their total out-of-pocket drug spending at $2,000 annually. But these protections don’t apply to people with private insurance or those without insurance. For non-Medicare patients, the Act doesn’t directly change how PBMs or states set generic drug prices.

What states have the lowest generic drug prices?

States with strong transparency laws and high pharmacy competition tend to have lower prices. California, Vermont, and Maine consistently rank among the lowest for out-of-pocket generic costs, thanks to PBM disclosure rules and cash-price access. Rural areas in states like Mississippi or West Virginia often have higher prices due to fewer pharmacies and less competition. GoodRx data shows price differences of up to 300% between neighboring states for the same drug.

Can I legally buy generic drugs from another state to save money?

Technically, yes-but it’s complicated. You can use mail-order pharmacies or online services like Cost Plus Drug Company that ship nationwide. You can also use GoodRx to find the lowest cash price near you, even if it’s in a neighboring state. But you can’t legally import drugs from other countries, and some states restrict out-of-state pharmacy dispensing. The safest and easiest way is to use a discount service that works in your state, not to physically travel to buy drugs elsewhere.

Shubham Pandey

December 3, 2025 at 00:10Same pill, different price. Welcome to America.

Carolyn Woodard

December 3, 2025 at 10:48The structural asymmetry between manufacturer cost and consumer outlay isn't merely a market inefficiency-it's a systemic extraction mechanism enabled by regulatory arbitrage. PBMs function as opaque rent-seekers, leveraging non-disclosure clauses to siphon rebates that should accrue to patients, while state-level Medicaid reimbursement models perpetuate geographic price discrimination via outdated benchmarks like WAC instead of NADAC. The result is a tiered pharmaceutical access paradigm where geography dictates therapeutic affordability.

Allan maniero

December 4, 2025 at 15:49You know, I’ve been thinking about this for a while-how we’ve turned something as basic as medicine into this labyrinthine financial game where the people who need it the most are the ones getting played the hardest. It’s not that the drugs are expensive-it’s that the middlemen have figured out how to make the system so confusing that no one knows who to blame, so no one does anything. And honestly? That’s the real scam. The fact that paying cash saves you 70%? That should be illegal. Or at least, it should make us all really angry. But we just shrug and swipe our cards.

Zoe Bray

December 6, 2025 at 12:35Pharmacy Benefit Managers represent a classic principal-agent problem wherein fiduciary obligations are systematically subordinated to profit maximization. The absence of statutory transparency mandates in 32 U.S. jurisdictions permits vertical integration between PBMs and retail pharmacies, thereby creating artificial market distortions. Empirical analyses from the USC Schaeffer Center corroborate that rebate retention, rather than pass-through, constitutes the primary driver of consumer overpayment. Legislative interventions must therefore prioritize PBM licensing regimes and mandate real-time price disclosure to restore market efficiency.

Sheryl Lynn

December 7, 2025 at 15:51It’s not just a system-it’s a *performance*. A grotesque, glittering cabaret of greed where the actors wear lab coats and the audience pays with their insulin. PBMs aren’t middlemen-they’re puppeteers with spreadsheets and non-disclosure agreements. And we’re the clowns who keep applauding while they pocket the circus ticket money. Bravo, capitalism. Encore.

Paul Santos

December 8, 2025 at 20:45So… we’re just supposed to use GoodRx now? 😅 Like, is that the new ‘buy local’? The pharmaceutical version? I mean, sure, it works-but it feels like being told to fix a broken bridge by walking around it. The real problem? We’ve outsourced ethics to algorithms and call it ‘innovation.’ 🤷♂️ #PBMscam

Eddy Kimani

December 10, 2025 at 08:22This is why I always check cash prices first now. I used to think insurance had to be better-turns out, it’s just more complicated. I saved $87 on my metformin last month just by using GoodRx. And honestly? The pharmacist looked at me like I was a genius. I just said, ‘I did the math.’ Turns out, the system doesn’t want you to. But you can still win.

John Biesecker

December 10, 2025 at 20:08man i just found out my insurance copay for levothyroxine is $22 but cash is $7?? like… what?? 😭 i feel so dumb for not knowing this sooner. i’ve been paying extra for years. i’m gonna tell my mom. she’s on 5 meds. she’s gonna lose it. also, cost plus drug co is legit. i ordered my stuff and it came in 3 days. no middleman, no drama. just pills. and a receipt that doesn’t make me cry.

Girish Padia

December 11, 2025 at 12:31India pays $0.50 for the same pills. We pay $45. And you call this freedom? This is corporate colonialism with a pharmacy receipt.

Elizabeth Farrell

December 12, 2025 at 15:03I know this sounds small, but asking your pharmacist ‘What’s the cash price?’ changed my life. I used to feel so powerless about my prescriptions-like I had to just accept whatever my insurance said. But once I started asking, I realized: they *want* you to know. They’re just not allowed to tell you unless you ask. So ask. Even if you’re shy. Even if you feel awkward. You’re not being rude-you’re being smart. And you’re not alone. Millions of us are doing this now. One question at a time, we’re rewriting the rules.

Genesis Rubi

December 14, 2025 at 13:16USA = best country in the world for medicine. If you can't afford your pills, you're just not trying hard enough. Go to Walmart. Or move to Canada. Or don't be lazy. Also, why are you even on meds? Maybe you just need to exercise more and stop eating carbs. 🇺🇸💪