By 2025, hepatitis B and C remain two of the most serious viral threats to global liver health - but the tools we have to fight them have changed dramatically. While hepatitis B has been preventable for over 40 years, millions still get infected every year. Hepatitis C, once a slow killer with harsh treatments, can now be cured in eight weeks with a single pill. The big problem? Most people still don’t know they’re infected.

How Hepatitis B and C Spread - And What Doesn’t Spread Them

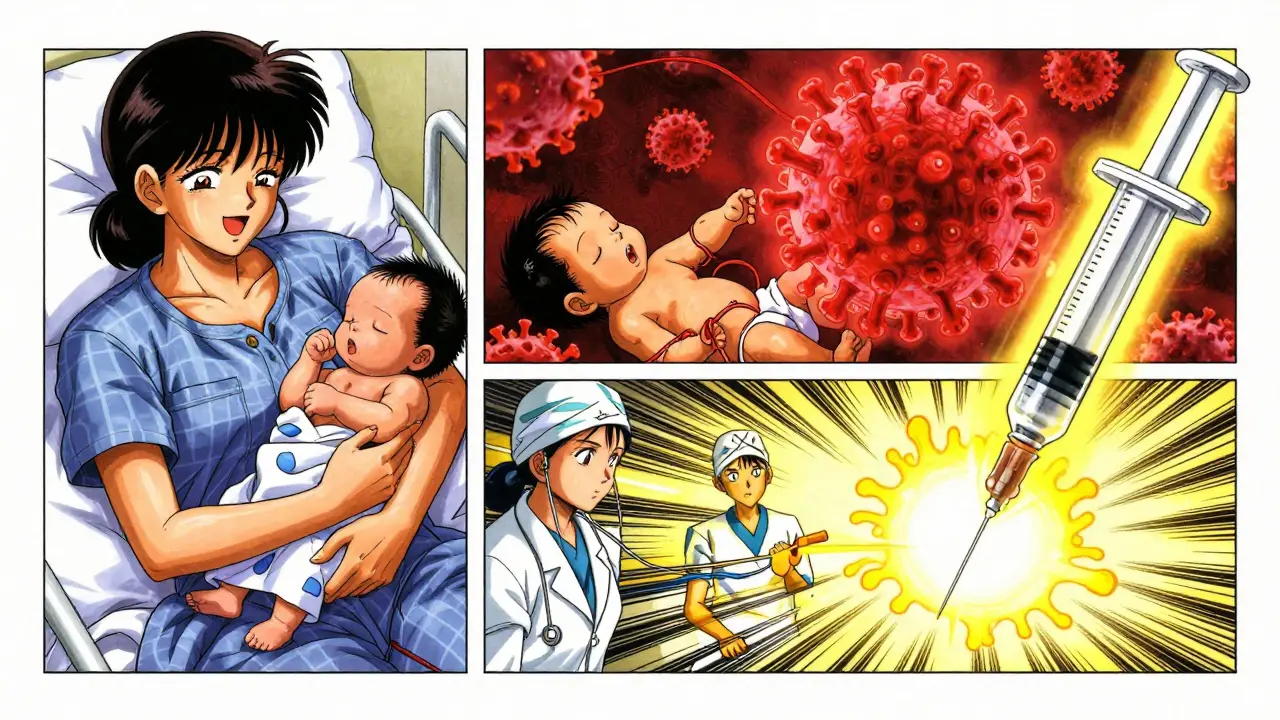

Hepatitis B is one of the most contagious viruses on the planet. You can catch it from blood, semen, vaginal fluids, or even saliva if it enters your bloodstream. That means childbirth is a major route: in places like sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia, up to 90% of chronic infections come from mothers passing the virus to newborns during delivery. It’s also common among people who share needles, have unprotected sex with multiple partners, or get tattoos with unsterilized equipment.But here’s what you don’t need to worry about: hugging, sharing food, using the same toilet, or being near someone who coughs. The virus doesn’t float through the air or live on doorknobs. It needs a direct path into your blood.

Hepatitis C is even more focused. It spreads almost exclusively through blood-to-blood contact. The biggest driver today? The opioid crisis. In the U.S., two-thirds of new hepatitis C cases between 2014 and 2018 happened in people under 40 who inject drugs. Needle sharing is the main culprit. It can also happen from unsterile medical equipment, tattoos, or even sharing razors or toothbrushes if they have a trace of blood.

Vertical transmission - mother to baby - happens in about 5-6% of hepatitis C pregnancies. That’s far lower than with hepatitis B, but still enough to make prenatal screening critical.

Who Should Be Tested - And When

The CDC now recommends everyone get tested for hepatitis C at least once in their life, starting at age 18. Pregnant women should be tested during every pregnancy. If you’ve ever injected drugs - even once, decades ago - you need a test. Same if you got a blood transfusion before 1992, have HIV, or have abnormal liver enzymes.For hepatitis B, the rules are a little different. Everyone should be screened at least once, but certain groups are at much higher risk:

- Healthcare workers and first responders

- People with multiple sexual partners

- Men who have sex with men

- People who live with or have sex with someone infected

- People from countries where hepatitis B is common (like parts of Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe)

- People in prisons or homeless shelters

- Those on dialysis or preparing for chemotherapy

Testing for hepatitis B isn’t one simple test. It’s a panel: HBsAg tells you if you’re currently infected, anti-HBs shows if you’re immune (from vaccine or past infection), and HBV DNA measures how much virus is in your blood. For hepatitis C, it’s simpler: first an antibody test, then an RNA test to confirm active infection. About 44% of people with hepatitis C don’t know they have it - that’s why universal screening matters.

Testing Has Gotten Faster - and Easier

Gone are the days of waiting days for lab results. Point-of-care tests now give answers in minutes. The OraQuick HCV test, approved by the FDA in 2010, uses a fingerstick and shows results in 20 minutes. New hepatitis B rapid tests have 98.5% sensitivity and 99.5% specificity - nearly as accurate as lab tests.These tools are changing lives in remote areas. In rural Australia, community health workers now carry test kits to outreach programs. In Egypt, mass screening campaigns cut hepatitis C rates from 14.7% in 2008 to under 1% by 2021. The same model is being tested in the U.S. Midwest, where opioid use has spiked infections in small towns.

Even more exciting? New tests like the Lumipulse G HBcrAg assay (approved by the FDA in 2023) can now measure core antigen levels - a potential marker for predicting who might achieve a functional cure for hepatitis B. It’s not yet available everywhere, but it’s a major step toward personalized treatment.

Hepatitis C: The Cure That Changed Everything

Before 2011, hepatitis C treatment meant months of painful injections, severe fatigue, depression, and a 40-50% chance of cure. Now? A single daily pill for 8 to 12 weeks. Drugs like Epclusa (sofosbuvir/velpatasvir) and Mavyret (glecaprevir/pibrentasvir) cure more than 95% of cases, regardless of genotype.These are called direct-acting antivirals (DAAs). They don’t just suppress the virus - they wipe it out. People who were told they’d live with hepatitis C for life are now virus-free. Liver damage can even reverse over time.

The cost used to be brutal. In 2014, a full course of sofosbuvir cost $84,000. Today, branded versions in the U.S. range from $24,000 to $30,000. But generics? In India, Egypt, or Bangladesh, you can get a full 12-week course for under $300. WHO and NGOs have pushed hard to make these available globally - and it’s working. Countries like Georgia and Rwanda have treated over 80% of their known cases.

Still, only 21% of people with hepatitis C in the U.S. got treated in 2020. Why? Lack of testing, stigma, insurance barriers, and fragmented care. Many people don’t know they’re infected. Others are afraid to go to a clinic. That’s why mobile testing units and community-based programs are now the front line.

Hepatitis B: No Cure Yet - But Better Control

Unlike hepatitis C, there’s no pill that clears hepatitis B. But we can control it - very well. Nucleos(t)ide analogues like tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) and entecavir suppress the virus so effectively that most people never develop cirrhosis or liver cancer. These drugs are taken daily, often for life.The biggest win? They also reduce transmission. When viral load drops, the chance of passing the virus to a partner or child drops dramatically. That’s why treatment isn’t just for the patient - it’s a public health tool.

Some patients - especially those with high HBsAg levels and no liver damage - are in the “immune tolerant” phase. In the past, doctors didn’t treat them. Now, guidelines suggest considering treatment if they have a family history of liver cancer, diabetes, or fatty liver disease. It’s a shift toward personalized care.

And there’s hope on the horizon. In 2025, over a dozen new therapies are in late-stage trials. siRNA drugs like JNJ-3989 silence viral genes. Capsid modulators disrupt how the virus builds itself. Therapeutic vaccines aim to wake up the immune system. One trial showed 10% of patients lost HBsAg - a functional cure - after 48 weeks of combination therapy. That’s still small, but it’s progress.

Right now, only 1-2% of chronic hepatitis B patients naturally clear HBsAg each year. We need better tools. But with today’s antivirals, most people can live normal, healthy lives - as long as they’re diagnosed and treated.

Why Vaccination Still Matters - Especially for Hepatitis B

The hepatitis B vaccine is one of the most effective public health tools ever created. It’s been available since 1982, and it’s safe, cheap, and lasts a lifetime. The WHO recommends the first dose within 24 hours of birth - especially in high-risk areas. In countries that follow this, mother-to-child transmission has dropped by 95%.Yet in the U.S., only 66.5% of adults have completed the full 3-dose series. That’s far below the 90% target. Why? Many people think they’re not at risk. Others forget the second or third shot. Some don’t know their doctor doesn’t automatically offer it.

Here’s the truth: if you’ve never been vaccinated, you’re at risk. Even if you think you’re careful. Hepatitis B can hide in your body for decades before causing damage. And once it’s chronic, it’s harder to treat.

There’s no vaccine for hepatitis C. That makes prevention even more critical: clean needles, safe sex, sterile medical care. But for hepatitis B, the vaccine is the shield. And we’re not using it well enough.

The Road Ahead: What Needs to Change

The science has won. We have the tools to end hepatitis B and C as public health threats. But systems haven’t caught up.For hepatitis C, we need to make testing routine - not optional. We need to remove insurance barriers. We need to bring treatment to people who use drugs, not wait for them to come to us. Programs that pair outreach workers with mobile clinics - like those in Sydney and Vancouver - are proving this works.

For hepatitis B, we need to get the birth dose to every newborn, everywhere. We need to screen immigrants from high-prevalence countries. We need to stop treating hepatitis B as a “foreign” disease. It’s here. It’s in Australia, the U.S., Europe - and it’s growing in younger populations because vaccination rates are slipping.

And we need to stop pretending that cost is the only barrier. Generic DAAs cost less than a monthly phone bill. Hepatitis B antivirals cost $6,000-$12,000 a year in the U.S. - but in India, they’re under $100. The problem isn’t the medicine. It’s access.

The WHO’s 2030 goal is clear: 90% fewer new infections and 65% fewer deaths. We can hit it. But only if we test everyone, treat those who need it, and vaccinate every baby. The science is ready. Now we just need to act.

Matthew Ingersoll

December 27, 2025 at 02:01Hepatitis C is now curable with a pill, but we still treat it like it’s a moral failing instead of a medical condition. The real epidemic isn’t the virus-it’s the stigma that keeps people from getting tested.

carissa projo

December 28, 2025 at 23:54It’s heartbreaking to think that a vaccine that’s been around since 1982 is still not routine for adults in the U.S. We vaccinate kids for chickenpox, measles, even HPV-but we act like hepatitis B is something that happens to ‘other people.’

It’s not about risk profiles anymore. It’s about equity. If we truly believe in prevention, we’d make the vaccine as accessible as a flu shot. No questions asked. No judgment. Just a needle and a chance to live without fear.

josue robert figueroa salazar

December 30, 2025 at 18:52Testing is free. Treatment is cheap. People still don’t get it. Stupid.

david jackson

December 31, 2025 at 01:53Let me tell you something that keeps me up at night: there’s a 12-year-old girl in rural Kentucky right now who was born to a mother who never got tested. She’s growing up thinking her liver is fine because she’s never felt sick. But the virus is there. Quiet. Patient. Waiting. And in 20 years, when she’s diagnosed with cirrhosis, no one will blink because we’ve normalized ignoring this disease.

Meanwhile, we’ve got miracle drugs that cost less than a new iPhone, and we’re still debating whether to fund mobile clinics in towns where people are dying because they’re too ashamed to walk into a hospital. This isn’t just public health failure-it’s a moral collapse.

Jody Kennedy

January 1, 2026 at 04:51I work in a community center and we started doing fingerstick HCV tests on Saturdays. People show up with their kids, grab a coffee, get tested while they wait. No one even thinks twice anymore. One guy came back two weeks later with his whole family-he got tested, his wife got tested, their 8-year-old got tested. He said, ‘I didn’t know I was a walking time bomb. Now I’m just trying to make sure nobody else is.’

That’s the power of normalizing this. Not fear. Not shame. Just care.

christian ebongue

January 2, 2026 at 19:36generic daas for 300 bucks? cool. now explain why my insurance still won’t cover it unless i prove i ‘used to’ shoot up. also why my dr still says ‘we don’t test for hbv unless you’re asian.’ lol.

jesse chen

January 4, 2026 at 01:03I just want to say thank you to whoever wrote this. It’s rare to see a piece that doesn’t just dump stats, but actually connects the science to the human story.

I lost my uncle to liver cancer from undiagnosed hepatitis B. He never knew he had it. He was a mechanic, never used drugs, never had multiple partners-just a guy who came here from Vietnam in the ‘70s and never got screened. We didn’t even know to ask.

This isn’t just about medicine. It’s about listening to people’s lives, not just their risk factors.

Joanne Smith

January 5, 2026 at 06:53They say hepatitis C is cured with one pill. But what they don’t say is that pill only works if you’re not homeless, not addicted, not uninsured, and not terrified of the medical system. The science is brilliant. The system? Still broken.

And yes-I’ve seen people get cured. But I’ve also seen people die because the clinic only opens two days a month and they had to miss two shifts to get there. That’s not a cure. That’s a privilege.

Prasanthi Kontemukkala

January 5, 2026 at 08:58In India, we have clinics that hand out hepatitis C pills at the same counter where they give out diabetes medicine. No stigma. No paperwork. Just health. The real lesson here isn’t the drug-it’s the system that delivers it. We don’t need more money. We need less bureaucracy.

Alex Ragen

January 6, 2026 at 13:35How quaint. We’ve reduced a complex, evolutionary biological phenomenon-viral persistence-to a series of pharmaceutical interventions and public health slogans. But we ignore the deeper epistemological crisis: why do we still treat disease as a problem of individual behavior rather than systemic neglect? The pill doesn’t cure capitalism.

Jay Ara

January 8, 2026 at 11:01my cousin got cured in bangladesh for 250 rs. here in usa i paid 15k and waited 6 months. same pill. different world.

Michael Bond

January 9, 2026 at 10:29Birth dose is the key. No excuses.

Kuldipsinh Rathod

January 10, 2026 at 11:08my dad had hbv and never knew. he died at 52. now i get tested every year. no big deal. just do it.